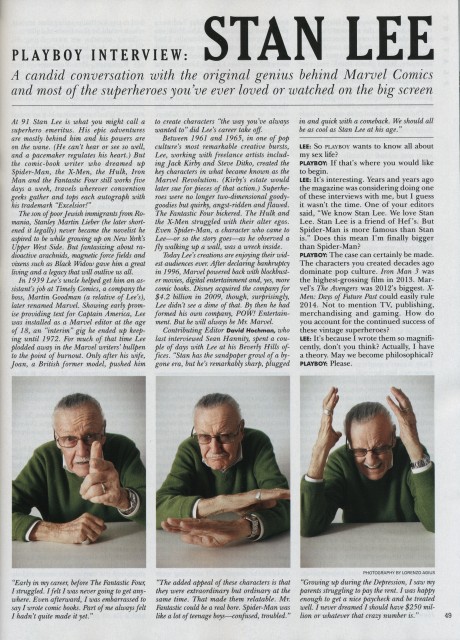

For the last few weeks, the world of comics has been buzzing about Playboy’s new interview with Stan Lee. It’s not that seeing Stan Lee’s name in the news is an earth-shattering event (barely a week goes by when he’s not appearing in some new commercial or movie, and it seems he’s constantly announcing new projects, appearing at conventions, and getting attention for bizarre concepts in his Spider-Man newspaper strip) – but there’s a few reasons this piece stands out.

First of all, there’s the publication in question. “Stan Lee In Playboy” is a headline that writes itself: the public face of comics interviewed in the world’s best-known adult magazine.

Additionally, The Playboy Interview is a holdout of long-form journalism in an era when “short and punchy” seems to be the goal of most media. Which means that this interview presumably digs a bit deeper than just another rapid-fire run through Stan’s usual stories and talking points.

Really though, what makes this article noteworthy is the overall tone, the way that Stan Lee drops a bit of the facade and shtick that has made him comics’ #1 icon, and presents a human side that most of us aren’t used to seeing. Various sources have commented on his relatively subdued mood, noted his willingness to address controversial topics, and mentioned that he portrays events in ways that don’t exactly fit with previous tellings.

(Though, to be fair, that last issue has nearly become one of Lee’s personal trademarks – he freely admits to having a terrible memory, and there are innumerable variations on even the best-known stories of his life. He wins listeners over with his enthusiasm and personality, not his grasp on dates, times, and facts.)

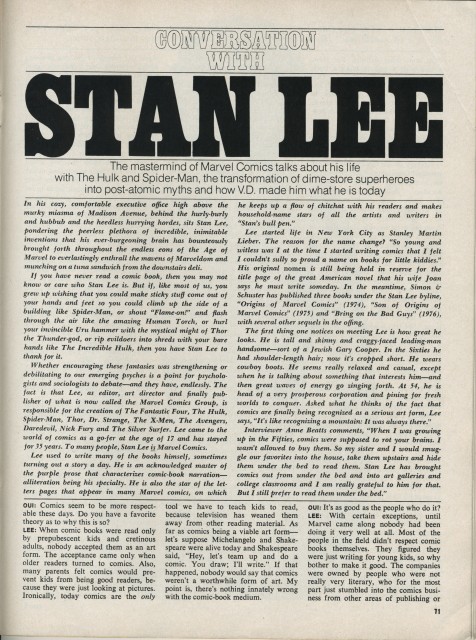

What struck me, though is that while this isn’t just another hype-and-fury “Smilin’ Stan” interview, it’s also not a total aberration – there are some other notable instances when Lee has been less guarded, diverged from the script, and talked a bit about himself. There’s the famous 1971 Rolling Stone article, a 1971 New York Times piece, and a cover story in a 1973 issue of Creem – but in particular, this recalls a 1977 interview Lee conducted with Oui, Playboy’s now-defunct sister publication.

I’m not sure whether Lee feels more open when in the context of an “adult magazine”, or whether it’s pure coincidence, but the Oui and Playboy articles reflect each other in unexpected ways, given the 37-year span between one and the other – there’s some fascinating symmetry, and some equally interesting contrasts. Both contain nearly identical versions of certain stories: Lee’s authorship of an anti-VD manual for the Armed Forces during World War II; Federico Fellini visiting the Marvel offices. Both touch on Lee’s earliest years, his theories of superheroics, and the roles Jack Kirby and other Marvel artists played in creating Marvel’s most iconic characters and stories. And in both, there are places where Lee seems unsure if he should be defending himself, or simply letting the readers form their own opinions.

In 1977, Lee was just beginning to step away from the world of print, and becoming the conduit between Marvel and Hollywood – in 1981 he would move to the West Coast and take on a full-time role trying to develop Marvel properties for film. Now, in 2014, Marvel is part of Disney, Lee’s co-creations have become the foundation for dozens of movies and TV shows, and Lee’s role is purely ceremonial, a (as he puts it) “pretty face they keep for the public”. In the Oui article, Lee is discussing his ambitions and goals outside of comics, the Lee of today seems to be making peace with what he has and hasn’t accomplished.

Both start out with softball questions and build slowly – the Oui conversation begins with a variation on Lee’s well-worn defense of comics’ artistic and literary merit: “Let’s suppose Michelangelo and Shakespeare were alive today and Shakespeare said “Hey, let’s team up and do a comic”…My point is, there’s nothing innately wrong with the comic-book medium.”

And the Playboy piece begins with Lee in similarly familiar territory, speaking on how comic stories follow in the traditions of grand myths and legends, and thus continue to appeal to generation after generation of readers.

An amusing bit of foreshadowing comes at the tail end of the Oui interview, as Lee discusses his plans for the future in oddly prescient fashion: “…my wife will never think of me as a writer until I write a story between two hard covers and have it made into a movie starring Robert Redford.”

In case you’re unaware, this year’s biggest hit movie is based in part on Lee’s work, features characters he co-created (in issues now reprinted in a beautiful hardcover edition) – and stars none other than, you guessed it, Robert Redford!

Both articles also touch on how classic Marvel comics were produced, and how creators were credited for their work. (For readers who aren’t familiar, Lee and his collaborators worked in what’s now commonly known as “the Marvel method”, where Lee gave artists a vague plot outline, then wrote the text and dialogue once he received the completed art. In Oui, Lee offers “I got better stories that way. Because all I was usually concerned with was the plot, not details.” And in Playboy, the interviewer puts Lee on the defensive, asking about the perception that he hasn’t properly credited his co-creators and how he could “do right by those guys once and for all”. Lee responds that he always tried to present his collaborators well, and ensured they were properly credited (“their names were always big as mine”), but he never was in charge of how much anybody got paid: “I would have liked to have gotten more money too.”

But the two articles really parallel when discussing how one of Lee’s earliest professional jobs was writing obituaries. In the Oui article, Lee explains that they were obituaries for living people, to be kept on file until needed, and that he moved on because “writing in the past tense about living people soon got to be very depressing” – a typically flippant way of addressing the topic.

Thirty-seven years later, his tone is a bit different. When the Playboy interviewer mentions that early employment, and asks Lee if he’s given any thought to what his own obituary might say, Lee’s reply is pensive, defensive, and somewhat resigned:

“I know mine is already written. It’s sitting there in the New York Times computers somewhere. It’s all ready to go. You can’t stop it. I’ve had a happy life. I don’t want anyone to think I treated Kirby or Ditko unfairly. I think we had a wonderful relationship. Their talent was incredible. But the things they wanted weren’t in my power to give them.”

And he goes on, waxing philosophical about his own mortality:

“Nothing lasts forever. Hell, I’m 91 years old. If I have to go while I’m talking to you, I’ve had a long enough life. I’d hate to leave my wife and my daughter, but heaven knows it’s beyond me. And I don’t even really believe in heaven.”

This sort of melancholy isn’t unheard of in Lee’s work – this is, after all, an author whose characters are given to dramatic monologues and crippling self-doubt, who took a bald metallic guy on a flying surfboard and transformed him into a contemplative fallen angel, soaring through the cosmos and commenting on the human condition. But it is a bit disconcerting when one realizes that this time, he’s not writing in the voice of a fictional creation. This is Stan Lee stepping out of character, and looking ahead toward the end. He’s not cleaning it up for the kiddies, he’s not dodging the difficult issues or editing for content. He appears to have some regrets (as most anyone with a 70+ year career in the entertainment industry would), but he also seems at peace with his place in the universe. He’s justly proud of his achievements, willing to speak openly about his life and work, and accepting that he can’t affect anyone’s impressions of him.

Of course, that’s not to say that you should come looking for a behind the scenes tell-all. Lee appears to be speaking straight from the heart, without his impresario uniform, but it’s still an interview in an international publication, and he’s still Stan Lee. He’s had decades upon decades of experience building a public personality, existing as a celebrity, and it would be foolish to assume he’d drop all his defenses now, for this one interview.

The man born Stanley Martin Lieber is someone that likely exists only in the privacy of his own home, and those of us who aren’t his close friends or family will never see completely behind his public face – but reading these two interviews is about as close as we’ll ever get. They’re fitting conversational bookends on the later years of Lee’s life and career, and when taken together, paint a complex and nuanced picture of a man who launched a thousand fantasies, co-created many of the 20th century’s most enduring characters, and along with a team of titanically talented collaborators, reinvented an American art form.